Despite all the social forces and cultural differences driving physics and visual art apart, the two fields share a remarkably similar existence. To begin with, they share the requirements of observation and description. Physicists strive to create descriptive equations and models for our environment. Likewise, artists make models and descriptions of the same environment, offering just as much insight and precision as equations. Fundamental principles of drawing are based on intense observation. It is a constant process of looking, marking, and then verifying the mark is correct. This feedback system is consistent with the process of physics. Both take perceptions and ideas and make them concrete by means of either equations or images.

The reality of the physical world is efficiently contained by mathematical equations because such statements define and present material without bias or emotion. They are statements of fact. This is useful for manipulating large entities of data and theories, but when it comes time to extrapolate this information back to the real world, data can become meaningless. The physicists' ability to see reality through all the mathematics is contingent upon a less scientific means of description. At this point, description becomes more subjective because the physicists must rely on their own perception of the situation.

As a physics student, I find these translations are fused with my ability to relate the physical situation to my body. I experience most physics problems with a first person perspective in my mind. For example, when thinking about the physical relationship of pressure and volume for a gas, in my mind I can increase pressure on a gas with a piston. I can push harder and harder and feel the pressure push back at me, perfectly balanced but furious. My mind's eye swirls around the scene of angry particles pushing back against my sweaty hands, and suddenly I feel all tingly and excited. My blood flows with a primordial urgency that Italo Calvino might appreciate.1 I have been able to sense a physical truth, within my body. It is an intangible sensation. It does not have a specific location, and it does not have any obvious physical manifestation. While emotion is often recognized by facial expressions or extreme feelings, this physical understanding I experience is significantly more nonspecific. I find I am often at a lack of words for describing it, resorting to gestures that don't always mean much to other people. I can rub a table surface, saying "yes, this is integration," but really it's a feeble attempt to explain the sensations of motion and counting that are running through my body.

This situation I've just described is the existence of the non-verbal world, and both physics and visual art reside there. The models that both teams make have the uniting factor of independence from the written word. Visual art is based in images; its own language is made of formal properties and artistic traditions. Physics is based in mathematics and diagrammatic space; a language that uses systems of symbols and operations to define and control ideas. In an absence of accompanying written explanations, both art and physics rely on the observers' abilities to make perceptions through the dynamics of non-verbal entities, such as imaginary sensations, inner senses of motion or bodily experiences of the physical world.

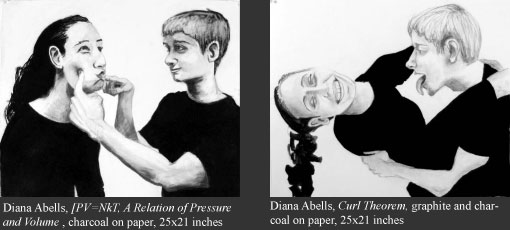

When I become more interested in my experience of understanding physics than the physics itself, I resort to art making. Making art allows me to capture the intangibles of physics, and life. Art's ability to investigate a broad range of subjects without the restrictions of scientific integrity and continuity gives it the authority to examine perspectives that are more subjective. My most recent work has developed after returning to the process of drawing. Drawing's immediacy and observational qualities strive to mix observation with subjective perception. It is this mix of the personal body with physical understandings of the world that I have tried to create in the artworks themselves.

My work this semester began with the initial goal of personifying the strange sensations and perceptions of the physical world I feel inside of me. I created a cast of characters to act out the narrative of my experiences of understanding physics at the primordial level. As my work took form in the three dimensional world of actual paintings and critics, I was able to gather feedback about how my story and sensations were coming across to an audience. This feedback was very significant in shaping the second and third phases of my work. It turned out that the characters I developed (which you will meet) were not dynamic enough to communicate the concrete story of my "physical" experience or any concepts of physics itself. The viewers were often distracted by the character's identities, their archetypal roles and their ambiguities. When it came time to begin new work, I ditched my original cast, and tried to simplify the work by translating my ideas into a new system of characters, in new spaces. I wanted something simple so that any physics I presented would be clear, and so that the character's identities would not distract from their actions and experiences within the drawings. I also took out references to the specific language of physics itself. I went back the simplicity of human bodies in narrative storytelling, in mainly charcoal and graphite, in order to be better connected with the push and pull of objectivity and subjectivity in drawing. In defining realistic surfaces and shapes, my hope is that the drawings presented in the SMP I exhibition will carry a familiarity of form to the viewers. By means of this familiarity with the body and figure, I hope that if they can feel the motion or pose of the figures in the images, then they can feel the physics concepts behind them.