Artist Statement | Sources | Bibliography | Image Gallery | Close Portfolio (and return to SMP 2006 Index)

The Royal Chincao Airforce (RCAF)

The Royal Chicano Airforce (RCAF) was founded in 1969 as an alternative way of presenting the goals of the Chicano civil rights movement. Their central mission was to use art as an organizing and unification tool (Noriega 27), creating a sort of art-based community making (Noriega 84). The RCAF was not just a group of artists: the members were also students, teachers, historians, thespians, and community organizers attempting to use the collective to its fullest and most creative potential (Noriega 26). Despite the shift of most Chicano art to mainstream galleries, the RCAF still exists and, after twenty-five years, is still intimately community involved (Favela 1).

The RCAF originated in Sacramento at USCS under the leadership of Esteban Villa and Jose Montoya, two professors in the ethnic studies department. They received their inspiration while attending the same school, under tutelage of El Ralph Orleans – a pinto poet, thief, revolutionary, and scholar (Noriega 28). The original group also included Ricardo Favela, Juanishi Orosco, Rudy Cuellar, and Louie “The Foot” Gonzalez (Favela 1).

The RCAF sought to make their projects intrinsically available to all members of the Mexican American community. These projects were to build a practical body of knowledge available as a reference for all Chicanos. To create their art, the RCAF threw away the colonial past and established alternate structures outside the mainstream (Martinez 1). One goal of theirs was to become a bicultural and bilingual arts center where artists could convene to support the community through education, events, and fulfilling communal needs (Visiones 1). The RCAF succeeded in this in 1972 with the founding of the non-profit Centro de Artistas Chicanos, a community-based arts organization that started a variety of offshoots, including a bookstore, a repair garage, and a cultural dance center (Favela 1). They sought political self-consciousness, educational advancement, and cultural understanding for all Chicanos (Martinez 1).

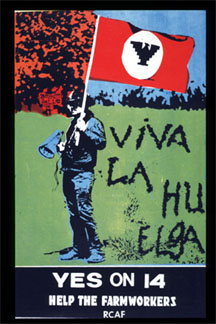

Best known for its murals, posters, and the works of individual members (Favela), the RCAF practiced resistance through humor. Originally known as the Rebel Chicano Art Front, the group changed its name based on the confusion of its initials with the Royal Canadian Airforce (Martinez). Playing off of this new title, the group decided to become the air command of the new Chicano nation. They used military imagery as a basis for much of their art, even going as far as addressing one another as “General” (Hernandez 126).

Believing that the best way to counter oppression is to mock it, the RCAF ensured that every part if its political involvement involved being as dramatic and outlandish as they believed necessary (Noriega 27). Combining universal revolutionary symbols, symbols of cultural affirmation, and a pervasive sense of humor (Noriega 86) resulted in a hectic, brightly colored, loud presentation that left the audience overwhelmed, convinced, and wanting more. The RCAF sense of humor can be seen in Louie “The Foot” Gonzalez’s “This is Just Another Poster” (advocating the boycott of Coors and Gallo wine) where he mocks the overwhelming number of posters produced by the Chicano movement and the Anglo response to them (Noriega 86). Another example is Montoya’s “Pachuco Art,” where the pacuhco, an idol of the Chicano movement, is depicted as a calavera (skeleton) (Noriega 105). The RCAF’s irreverence extended even to their own culture and beliefs.

Along with this irreverence went a constant questioning of media and style. The RCAF was interested in mixing artistic styles and techniques because of the implications it had for their Mestizo identity. For example, Louie “The Foot” Gonzalez began as a poet working in concrete poetry. On joining the RCAF, he became interested in silk screening and experimented with that. Not feeling fulfilled with either, he combined the two to enhance one another (Keller 298).

The poster was one of the RCAF’s main artistic forms because of its accessibility and counter-cultural significance. Poster art was the only medium readily available to the members that could be easily displayed in the barrio, their only available venue (Noriega 73). It was the best form for quick mass-dissemination, since a huge number of copies could be made from one original fairly quickly. Posters could be displayed anywhere, from the home and office to the streets. The temporary nature of posters allowed them to be used for time-sensitive announcements as well as creating an ever-changing decorative scene. Additionally, RCAF poster art functioned to nurture collective memory, cultural pride, and solidarity of other oppressed people of color around the world. The restrictions of the poster format to attract attention and communicate quickly and concisely led the RCAF members to push themselves to new creative levels (Noriega 72).

Since the heyday of Chicano activism, Chicano art has bee co-opted by art writers, reviewers, and curators as a kind of primitivist-chic. However, the RCAF is still working within the community. The organization still works with the United Farm Workers and has recently worked to create the Chicanos for Political Awareness (Cornejo 1). The members consider their job to be spreading the word to the barrio, and the best way to do this is through involving the whole community. They are misconceived as being antiquated, but this is because their goal was never to get into the mainstream. Despite negative views and their limited celebrity, the RCAF has inspired younger generations to take to the streets and exercise their creativity and freedom of speech. These new groups have taken the RCAF poster format and transferred it to T-shirt designs to create a sort of “roving poster” (Noriega 35).

I find myself intrigued by the RCAF because of their dedication to community work, but at the same time I am attracted to them for their wildness and counter-cultural dynamic. Those things seem contradictory, but in many ways are not. The outlandish has the ability to push people away, but it also has the ability to suck them in, to draw attention and hold it. If you are trying change the current culture norms, involving the community is not enough. You have to lead by example, show people that living outside the box can be fun and interesting. Some people might be estranged, but you will definitely make more people think. The collective is an idea that I have been playing with for quite a while now, and I am coming to think that it is the best way to get things done while also questioning traditional cultural values. If well organized, the individuals in a collective fill in the holes in each other’s abilities and understanding. Everyone grows, and this fuels the collective to be stronger. I am drawn to the idea of the poster because of its capabilities, the ease of instructing others how to make them, and my background in pop art. Maybe I should do a poster workshop. I am not going to try to be like the RCAF, as I come from a different era and walk of life with different concerns, but I would consider lifting some of their ideas and appropriating them. I’m sure they would not mind.